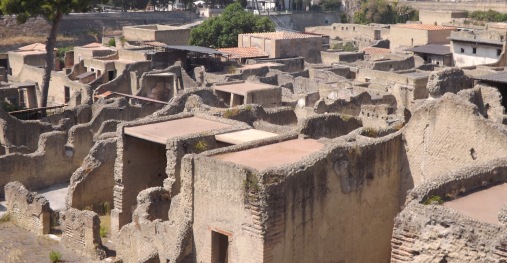

Earlier this week I had the great privilege to spend an hour in a room full of engaged and enthusiastic Year 9 students talking about Pompeian graffiti. These students are studying for a GCSE in Classical Civilsation after school as part of The Iris Project at Cheney School. During the paper, in which I was introducing them to various aspects of graffiti and dipinti and the ways historians use these inscriptions, I was asked a question that rather took me by surprise. It wasn’t about graffiti, but about a wall painting that I was using to illustrate an event in Pompeii’s history which is related to a number of graffiti.

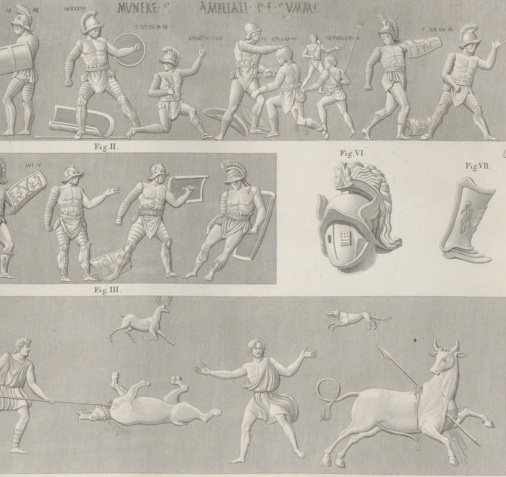

This painting, found in the House of Anicetus, ( I.iii.23 ) famously depicts the riot that took place in the amphitheatre in AD 59. We know this is a real event because Tacitus tells us about it:

Tacitus Annals 14.17

‘At around the same time, there arose from a trifling beginning a terrible bloodbath among the inhabitants of the colonies of Nuceria and Pompeii at a gladiatorial show given by Livineius Regulus, whose expulsion from the senate I have recorded previously. Inter-town rivalry led to abuse, then stone-throwing, then the drawing of weapons. The Pompeians in whose town the show was being given came off the better. Therefore many of the Nucerians were carried to Rome having lost limbs, and many were bereaved of parents and children. The emperor instructed the senate to investigate; they passed it to the consuls. When their findings returned to the senators, the Pompeians were barred from holding any such gathering for ten years. Illegal associations in the town were dissolved, Livineius and the others who had instigated the trouble were exiled.’

In addition, there are a number of graffiti that illustrate the kind of animosity between neighbouring towns that may have contributed to, or resulted from, the event that Tacitus describes.

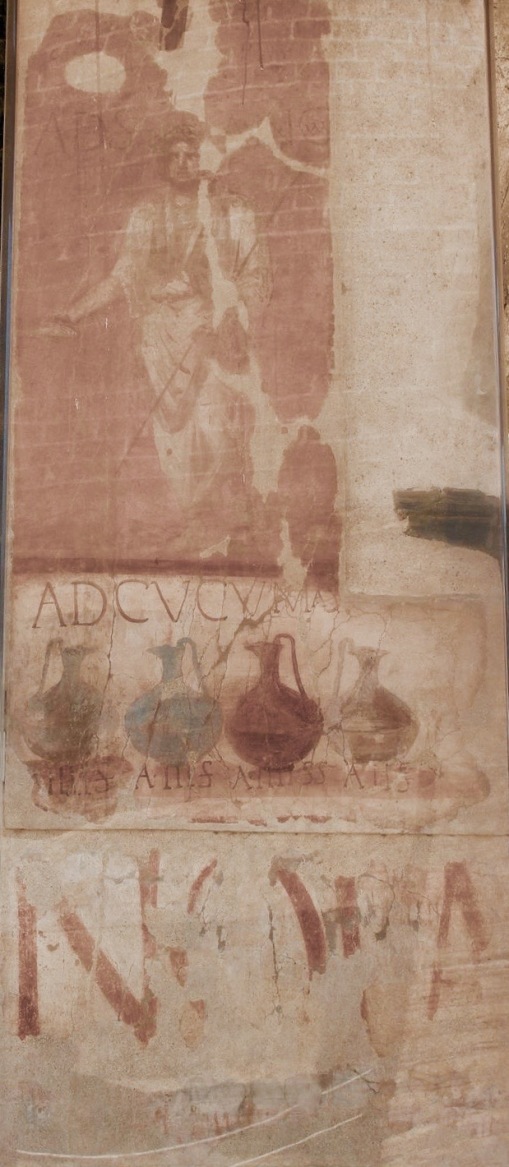

CIL IV 2183

Puteolanis Feliciter / omnibus Nuc{h}erinis / felicia et uncu(m) Pompeianis / Petecusanis.

‘Good fortune to the Puteolans; good luck to all Nucerians; the executioner’s hook to Pompeians.’

CIL IV 1329

Nucerinis / infelicia.

‘Ill luck to the Nucerians.’

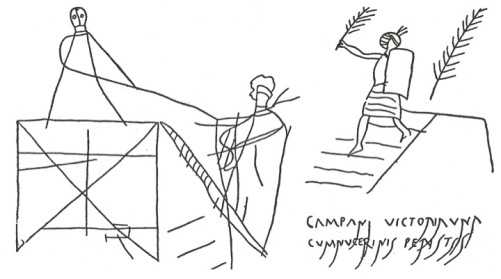

One even accompanies a drawing depicting a gladiator holding a palm of victory:

CIL IV 1293

Campani victoria una / cum Nucerinis peristis.

‘Campanians, in our victory you perished with the Nucerians.’

The question that was asked, however, related not to the graffiti but to the painting itself, or more to the point, how unusual it was to have a painting in one’s house that depicted such violence. On most occasions when I have come across a reference to this painting in a scholarly work, if the oddness of it is mentioned at all, it is done in a very offhand way of wondering why someone would wish to commemorate such an event (even if the Pompeians were considered the victors). I have never come across a comparison to other wall paintings in terms of the nature of the violence illustrated. In the moment when the question was asked, I was racking my brain for a similar scene – and I couldn’t think of a single one. The closest may be the Alexander Mosaic from the House of the Faun, which depicts a military battle. Still, as detailed as it is in regards to fallen men and distressed looking horses, it does not depict seemingly dead bodies still on the ground as we can see in the painting from Anicetus’s house. The very nature of gladiatorial combat is a gruesome and bloody sport to which Romans were largely accustomed, but sitting in an arena watching a contest which may result in spilled blood (but, contrary to popular belief, rarely death) is quite a different thing than displaying images of the dead or dying on the wall of your house.

The question, as raised by this student, made me think about the painting in a different way, and really wonder about the mindset of the person who had it commissioned. (I am now extremely curious to see if I can find anything comparable on the wall of a Roman house. If anyone has any examples – do let me know.) This has been on my mind for a number of days, not just because of the nature of the question, but because of who asked it. It was a timely (and to be honest, necessary) reminder that for as much as I know and continue to learn about the ancient world, there is always a new and interesting way to think about things. More to the point, it is more often than not our students who point us in a different direction, and that our research, without our students, is lacking something essential.