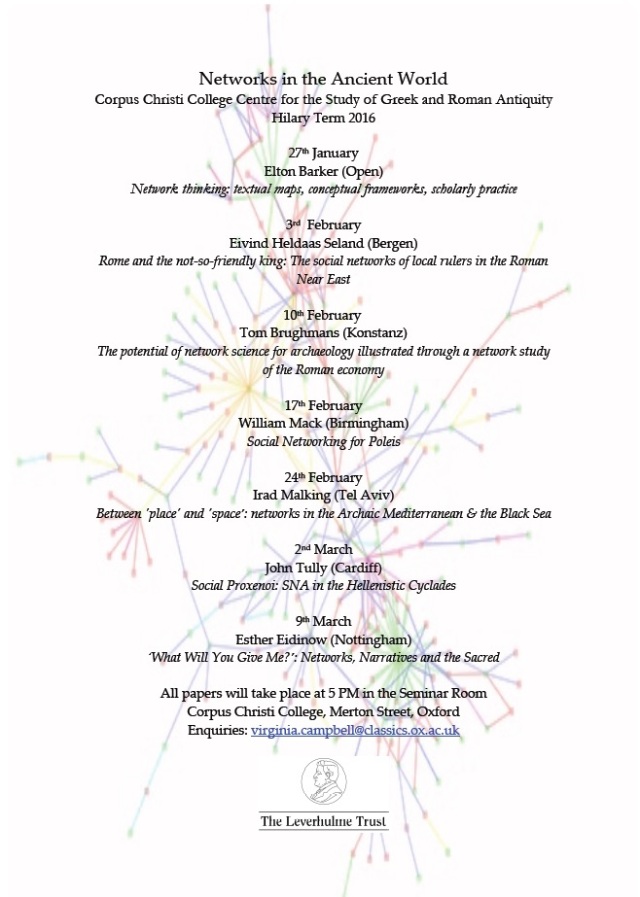

I am pleased to present, in conjunction with the Corpus Christi College Centre for the Study of Greek and Roman Antiquity as part of my Leverhulme Trust ECF, a seminar series on networks in antiquity. Seminars are held on Wednesday at 5 pm. All are welcome to attend. Please contact me for further information.

Tag: Economy

Black Friday

In the U.S., today, the Friday after Thanksgiving, is commonly known as Black Friday – a retailers dream (or nightmare) – as it is the day that traditionally kicks of the Christmas shopping season. It has become so ubiquitous a term, it began to appear in advertisements for sales here in the U.K. last year, and this year, has begun more than a week in advance of the day itself (and let’s not even discuss the number of emails I’ve had today from various shops). Whilst the last decade or so has shown a dramatic shift to shopping online rather than actually leaving the house, in the past, both recent and distant, shopping, for foodstuffs at the very least, was virtually a daily activity.

Shopping for various goods – pots, clothing, shoes, food items – is part of a lively scene depicted in a wall painting that shows the Forum. Found in the Praedia of Julia Felix (II.iv), this is often used as an illustration of the activities of daily life in Pompeii.

It is not clear if this painting represents a nundina (market day) or just an average day. It is believed that the large regional market days would have been held in or around the amphitheatre, which is a significantly bigger space. There are a series of painted inscriptions that seem to demarcate areas for particular stall holders in arcades of the amphitheatre, such as this example:

CIL IV 1096

Permissu / aedilium Cn(aeus) / Aninius Fortu/natus occ(u)p(avit).

‘By permission of the aediles Gnaeus Aninius Fortunatus occupies (this space).’

The market was a regional one, moving from town to town on set days. A text from a shop (III.iv.1) provides the calendar:

CIL IV 8863

Dies / Sat(urni) / Sol(is) / Lun(ae) / Mar(tis) / Merc(urii) / Iov(is) / Ven(eris) // Nundinae / Pompeis / Nuceria / Atilla / Nola / Cumis / Put<e>olis / Roma / Capua // X[VIIII] / X[VIII] / X[VII] / XV[I] / XV / XIV / XIII / X[II] / XI / X / VIIII // VIII / VII / VI / [V] / [I]V / [I]II / II / pr(idie) / K(alendae) / Non(ae) / VII / VI // Non(ae) / VIIII // VIII / VII / VI / V / IV / III / pri(die) / Idus // I / II / III / IV / V / VI / VII / VIII / VIIII / X / XI / XII / XIII / XIV / XV / XVI / XVII / XVIII / XVIIII / XX / XXI / XXII / XXIII / XXIIII / XXV / XXVI / XXVII / XXVIII // XXVIIII / XXX.

Day Markets

Saturn Pompeii, Nuceria

Sun Atella, Cumae, Nola

Moon Cumae

Mars Puteoli

Mercury Rome

Jove Capua

Venus

Whether the person who scratched this into the wall was using this as a personal or commercial reminder is unclear. Information about the purchase and sale of goods, including slightly fluctuating prices depending on the day, is detailed in an inscription (IX.vii.24–5). Found in the atrium of a inn, attached to a bar next door, this graffito was clearly the inventory list of the owner/operator.

CIL IV 5380

VIII Idus casium I / pane(m) VIII / oleum III / vinum III / VII Idus / pane(m) VIII / oleum V / cepas V / pultarium I / pane(m) puero II / vinum II / VI Idus pane(m) VIII / puero pane(m) IV / halica III / V Idus / vinum domatori |(denarius) / pane(m) VIII vinum II casium II / IV Idus / Hxeres |(denarius) pane(m) II / femininum VIII / tri<t>icum |(denarius) I / bubella(m) I palmas I / thus I casium II / botellum I / casium molle(m) IV / oleum VII / Servato / montana |(denarius) I / oleum |(denarius) I VIIII / pane(m) IV casium IV / porrum I / pro patella I / sittule(m) VIIII / inltynium I / III Idus pane(m) II / pane(m) puero II / pri(die) Idus / puero pane(m) II / pane(m) cibar(em) II / oleum V / halica(m) III / domato[ri] pisciculum II.

‘7 days before the Ides cheese 1, bread 8,oil 3, wine 3.

6 days before the Ides bread 8, olive 5, onion 5, cooking pot 1, bread for slaves 2, wine 2.

5 days before the Ides, bread 8, bread for slaves 4, porridge 3.

4 days before the Ides, (unknown type of wine) 1 denarius, bread 8, wine 2, cheese 2.

3 days before the Ides [?] bread 2, female? 8, wheat 1 denarius, beef? 1, dates 1, incense 1, cheese 2, small sausage 1, soft cheese 4, oil 7.

For Servatus [unknown item], oil 1 denarius, 8 bread 4, cheese 4.

Leek 1, for a small plate 1, [two unknown items].

2 days before the Ides, bread 2, bread for slaves 2.

1 day before the Ides, bread for slaves 2, plain bread 2, leek 1.

On the Ides plain bread 2, oil 5, porridge 3, whitebait 2.’

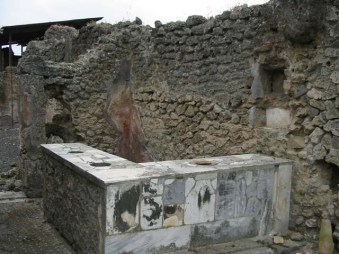

Besides functioning as accommodation for the night, the various taberna and thermopolium found in abundance in Pompeii such as this one served both hot and cold food. The counter tops, such as the one located in this building, are more often than not the identifying feature of such services.

Their prevalence in Pompeii, as established by Steven Ellis, and still part of ongoing fieldwork by the Pompeii Food & Drink Project, has led to the conclusion that many of the city’s residents may have been getting their hot meals from such facilities, and did little cooking at home. That bread was a daily purchase has long been established: the large number of mills and bakeries in the city is well documented (thirty-three is the current tally). Selling bread is, in fact, commemorated in another wall painting, this one found in the (understandably named) House of the Baker (VI.iii.3).

There is additional evidence bread was sold from temporary stalls around the city, and not just for personal consumption. Two graffiti from the Temple of Apollo inform us that man named Pudens and Verecunnus were selling libarius, bread used in sacrifice (CIL IV 1768, 2769). The sale of other food items, particularly wine and garum, the fermented fish sauce so popular in Roman cooking, can be found on the amphorae recovered in excavation. These were typically marked with abbreviated texts indicating the name of the producer or owner, the origin, and contents of the jar.

CIL IV 9406

G(ari) f(los) scombr(i) / Scauri / ex officina Scauri / ab Martiale Aug(usti) l(iberto).

Scaurus’ finest mackerel sauce from Scaurus’ workshop by Martial, imperial freedman.

Garum manufactured by the Umbricius family was a particularly popular item both locally and elsewhere: approximately 23% of the jars containing fish sauce that have survived antiquity come from the Pompeian factory. The tituli picti are even commemorated in a mosaic in the Umbricii house (VII.vi.16).

Evidence for the buying and selling of other items that don’t necessarily survive as objects, such as textiles and luxury items like jewellery, can be found in some of the tablets of Iucundus as well as other graffiti. Items were either auctioned off or, occasionally, used as surety for borrowing funds. One example of this is recorded in a graffito in which a woman, who seems to be acting much like a modern pawnbroker, offers a loan in exchange for a pair of earrings:

CIL IV 8203

Idibus Iuli(i)s / inaures pos(i)tas ad Faustilla(m) / pro |(denariis) II usura(e) deduxit aeris a(ssem) / ex sum(ma?) XXX.

’15 July. Earrings deposited with Faustilla. Per two denarii she took as usury one copper as. From a total (?) 30.‘

Fortunately for the Pompeians, it seems they didn’t go in for the insanity of modern special sales, but went about their shopping, whether daily necessities or luxury items, with little fuss. Like most pre-industrial societies, for the majority of people, shopping was based on current necessity, and was done in moderation. Perhaps this changed in times of crisis, particularly when there were shortages of grain, when riots and fighting are recorded in Rome. Last I checked, however, there was no shortage of giant tellies or iPads. Maybe we should follow the ancient example and make this Friday a little less black.

Can I Get a Witness?

The wax tablets of Lucius Caecilius Iucundus are one of the best records for financial activity that survive antiquity. The tablets, triptychs of wooden leaves covered with wax and tied together to make six pages, were used as receipts, closed, wrapped with string, and sealed by witnesses. Carbonised by the Vesuvian eruption in AD 79, these 153 tablets were found in the House of Caecilius Iucundus at V.1.26 during its excavation in 1875. The tablets record a number of transactions, including auctions, money lending, and payment of civic rents. What makes these records so important for network analysis is that each one of these exchanges made use of a number of signatories – typically six in addition to those directly involved in the transaction – who acted as witnesses to the transaction taking place.

The use of so many witnesses, is, of course, what makes the tablets so valuable for the purposes of building a network for Pompeii. Not only do they provide information about the workings of the local economy, but more importantly, they contain so many names. Whether or not these witnesses were friends, business associates, or simple happened to be passing by at a particular time when signatories were needed is difficult to determine without looking for corroborative evidence amongst other bits of Pompeian epigraphy. Regardless, the tablets can be used to trace both individuals and events (if one views the signing as an event), which actually allows for the analysis of both one and two mode networks.

I can hardly cover all of the tablets of Iucundus in a single post, but this instead serves as a brief example of how the tablets can be used, starting with just one individual. I selected the six wax tablets on which Aulus Veius Atticus appears as a witness. If we look at the individual texts, some of which are more complete than others, you can see that, typically, the witnesses are appearing in the third or fourth section.

CIL IV 3340.22 05. November AD 56

Perscriptio Histriae Ichmadi || HS n(ummum) VI(milia)CCCCLVIs(emis?) / quae pecunia in / stipulatum L(uci) Caecili / Iucundi venit ob / auctionem Histriae / Ichimadis mercede / minus persoluta || habere se dixsit / Histria Ichimas ab / L(ucio) Caecilio Iucundo. / Act(um) Pomp(eis) Non(is) Nove(mbribus) / L(ucio) Duvio P(ublio) Clodio co(n)s(ulibus). / C(ai) Numitori Bassi / L(uci) Numisi Rari / A(uli) Vei Attici / D(ecimi) Caprasi Gobi[onis] / L(uci) Valeri Peregr(ini) / [—] Cestili Philod(emi) / [C(ai)] Novelli Fortun(ati) / [A(uli)] Alfi Abasca[nti] / [L(ei)] Cei Felic[ionis] || [L(ucio) Duvio P(ublio) Clo]dio co(n)s(ulibus) / [Non(is) Nove]mbr(ibus) / [— sc]ripsi rogatu / [Histriae Ichimadis ipsi] persoluta / [esse ab L(ucio) Iuc]undo HS n(ummum) / [sex milia quadr]i(n)gentos quinqua / [ginta sex semi]s ob auctionem /q[uam servus] eius fecit [act(um) Pom]peis.

CIL IV 3340.35 05. August AD 57

Per[s]c[ript]io Cn(aeo) Alleio / C(h)ryser[oti] || [HS n(ummum)] / III(milia)DXI / quae pecunia in / stipulatum L(uci) Caecili / Iucundi venit ob / auctionem Cn(aei) Allei C(h)ryserotis / mercede [m]inus / persolu[ta h]abere / se dixsit [C]n(aeus) Alleius / C(h)ryseros [ab] L(ucio) Caecilio / Iucundo. / Act(um) Pomp(eis) Non(is) Aug(ustis) / Nerone Caes(are) II L(ucio) Calpurn(io) c(onsulibus) || [—] Postumi Primi / A(uli) Appulei Severi / [A(uli)] Vei Attici / [— Au]rel(i) Vitalis / T(iti) [Sorni] E[u]t[y]ch[i] / L(uci) Corneli Maxsi(mi) / P(ubli) Terenti [—] / N(umeri) Popidi Am[—].

CIL IV 3340.49

Perscriptio [L(ucio) Cornel]io Ma[xs(imo)] [—] || L(ucio) Caecilio [—] / act[um || HS n(ummum) V(milia)CCC quae pecunia in stipulatum. / L(uci) Caecili Iucundi venit ob manc[i]pia / duo veterana vendita r(atione) hereditaria / L(uci) Corneli [Tert]i soluta habere se / [dixi]t L(ucius) Cornelius Maxsimus / ab L(ucio) Caecilio Iucundo. || [—] Postumi Primi / A(uli) Appulei Severi / [A(uli)] Vei Attici / [— Au]rel(i) Vitalis / T(iti) [Sorni] E[u]t[y]ch[i] / L(uci) Corneli Maxsi(mi) / P(ubli) Terenti [—] / N(umeri) Popidi Am[—].

CIL IV 3340.67

Perscriptio N(umeri) Popidi [—]Y[—] || [HS] n(ummum) V(milia)[—] / quae pecunia in / stipulatum L(uci) Caec[ili] / Iucundi venit o[b] / auctionem N(umeri) [P]op[idi] || [Pop]idi[us(?) —] / [ab Caecilio] Iucundo || Q(uinti) Appueli Severi / A(uli) Vei Attici / P(ubli) Terenti Primi / L(uci) Cei Decidiani / [—] Corneli Adiutoris / L(uci) Lucili Fusci / C(ai) Corneli Tagetis / [—]O[—].

CIL IV 3340.99

[Persc]riptio P(ublio) Terentio Prosod(o?) || Q[—]C[—] || Ti(beri) Claudi Nedymi / Q(uinti) Appulei Severi / A(uli) Vei Attici / M(arci) Aureli Vitalis / [N(umeri) Popid]i Sodalion[is] / [—]pi Fortunati / [P(ubli) Si]tti Zosimi / [P(ubli) Tere]nti Prosodi.

CIL IV 3340.115

[—] / A(uli) Vei Attici / M(arci) Uboni Cogitati / C(ai) Cas[si] Secundi /[L(uci) Va]leri Peregrini / [P(ubli) Corne]li Tagetis / [—].

There are 35 names all together on these 6 tablets (excluding consuls used solely for dating purposes), but including Lucius Caecilius Iucundus, who was presumably present for most (if not all) of the transactions:

1. Lucius Caecilius Iucundus (22, 35, 49, 67, 99, 115)

2. Aulus Veius Atticus (22, 35, 49, 67, 99, 115)

3. Histria Ichimas (22)

4. Gaius Numitorius Bassus (22)

5. Lucius Numisius Rarus (22)

6. Decimus Caprasius Gobio (22)

7. Lucius Valerius Peregrinus (22)

8. [—] Cestilius Philodemus (22)

9. Gaius Novellius Fortunatus (22)

10. Aulus Alfius Abascantus (22)

11. Lucius Ceius Felicio (22)

12. Lucius Laelius Fuscus (35)

13. Marcus Fabius [—] (35)

14. Publius Terentius Primus (35, 49, 67, 99)

15. Lucius Vettius Valens (35)

16. Gaius Poppaeus Fortis (35)

17. Tiberius Caudius Secundus (35)

18. Aulus [—] Fuscus (35)

19. Gnaeus Alleius Chryseros (35)

20. Lucius Cornelius Tertius (49)

21. Lucius Cornelius Maxsimus (49)

22. [—] Postumius Primus (49)

23. Aulus Appuleius Severus (49)

24. [— Au]relius Vitalis (49)

25. Titus Sornius Eutychus (49)

26. Numerius Popidius Am[—] (49)

27. Quintus Appuleius Severus (67, 99)

28. Lucius Ceius Decidianus (67, 99)

29. [—] Cornelius Adiutor (67, 99)

30. Lucius Lucilius Fuscus (67, 99)

31. Gaius Cornelius Tages (67, 99)

32. Marcus Ubonius Cogitatus (115)

33. Gaius Cassius Secundus (115)

34. Lucius Valerius Peregrinus

35. Publius Cornelius Tages (115)

Of these, there are six men in addition to Atticus who appear more than once. More to the point, all nine of the witnesses who appear on tablet 67 also appear on 99, which suggests that these two transactions might have actually been carried out at the same time, with the same witnesses present to sign off on both sales. We can see a wide range of known Pompeian gentilicium present in the witnesses – Cornellii, Ceii, Poppidi – but if we look closer at the cognomen in particular, these are not the men of these families known from electoral campaigns, and are more likely to be freedmen. The cognomina do include a number of Greek names as well as those favoured for the servile classes, and although this certainly warrants further investigation, it does seem more likely than not that there are a number of freedmen serving as witnesses.

In terms of finding the ancient network, it is (seemingly) a simple process to take this much further using solely the wax tablets. To demonstrate this I picked two men from this list who appear more than once. Publius Terentius Primus seems the most obvious choice because he appears on four tablets with Atticus, thus suggesting a possible strong tie between the two men. He actually appears on sixteen additional tablets, connecting him with 97 others witnesses or sellers, so in all, well over a hundred people when you include the tablets he is on with Atticus. Whether this actually indicates a strong tie with Atticus or a strong tie with Iucundus remains to be seen.

The other selection is Quintius Appuleius Severus, because I found him on Tablet 25, on which Primus also appears. So in addition to two tablets with Atticus, and one with Primus, Severus appears on another 14 tablets with a further 100 individuals.

Just by looking at the appearances of these men as witnesses on the wax tablets, there is already a network of more than 200 individuals that can be connected through three nodes. This does not yet even take into account further epigraphic information. If we include the epitaph of Aulus Veius Atticus, for example, we can add in the 8 other members of the gens Veia, the 7 other Augustales, and the family of Gaius Munatius Faustus and Naevoleia Tyche, with whom Atticus built a tomb, which adds another 12 people from their funerary inscriptions alone. Add in the extended family groups of the Munatii and the Naevoleii, and we now have a network with close to 300 actors, all of whom can be connected through one line, and many of whom can be connected along multiple edges to different actors within the network. This demonstrates a fruitful network analysis, especially when incorporating multiple forms of epigraphic (and to some extent) archaeological material. Eventually, I hope the network I can map will thus link most of the men and women found in the epigraphic material of Pompeii, thus providing us with a clear view of how the society in this ancient city actually functioned.

I think I’m going to need a bigger piece of paper.

Pompeii Research Seminar Series: Dr. Richard Hobbs

Dr. Richard Hobbs, Curator of the Romano-British Collections at the British Museum, gave the third lecture in the research seminar series Pompeii: The Present and Future of Vesuvian Research with a paper entitled ‘Coins and Mediterranean connections in early Pompeii.’

Dr. Hobbs is an expert on Iron Age and Roman metalwork, including coins, jewellery and dining ware. He has written about the treasure of Mildenhall – ‘Platters in the Mildenhall Treasure’ Britannia (2010) – and metal deposits – Late Roman Precious metal deposits, AD200-700: changes over time and space, BAR Int Series (2006). He has overseen the study of the coins recovered by the Anglo-American Pompeii Project, recently publishing the results of this work: Currency and exchange in ancient Pompeii. Coins from the AAPP excavations at Region VI, Insula 1, Institute of Classical Studies, BICS Supp. (2013). A list of his further publications can be found here.

Recorded on the 5th of March 2014 at the University of Leeds.