I recently came across what is quite likely the earliest treatise to appear on Pompeian graffiti: Inscriptiones Pompeianae; or Specimens and Facsimiles of Ancient Inscriptions discovered on the walls of buildings at Pompeii. Published in 1837, this small volume penned by Charles Wordsworth, nephew of the famous poet, Classicist, and bishop of St. Andrews, is, if not always entirely accurate in its interpretation of the texts, nonetheless an altogether lovely presentation of the texts scratched into the walls of the ancient city.

A mere thirty-three pages, this slim volume takes the form of a letter Wordsworth addresses to a friend – his dear P—, who seemingly accompanied him on a trip to Pompeii in 1832. He states the letter is ‘retaliation’ for P, who indulged in ‘some pleasant humour’ for his interest in the graffiti they saw on their trip. He further writes that he ‘should indeed have abstained from this undertaking as unnecessary, had any notice whatever been taken of these fragments to which I now invite your attention, by any of the writers who have described the antiquities of Pompeii.’ He claims (rightly) that apart from a few vague references in William Gell’s revised 1832 publication of Pompeiana, no one has yet mentioned the texts in print, much less published them in any way. This then, is what he sets out to do.

Wordsworth invites P to join him, as he acts as guide, to go back through the streets of Pompeii, and examine more thoroughly a number of the ancient graffiti. Likely to pique the interest of his friend, Wordsworth begins with a text from Vergil, P’s favourite Latin poet, which is to be found on a wall in the Building of Eumachia.

Now recorded as CIL IV 1982 (CLE 1785 = CLE 2292):

Carminibus

Circe socios

mutavit

Olyxis

the graffito is line 70 from Book VIII of Vergil’s Eclogues, the entire stanza (lines 69-71) of which reads:

Carmina vel caelo possunt deducere lunam,

carminibus Circe socios mutavit Ulixi,

frigidus in pratis cantando rumpitur anguis.

‘Songs can even draw the moon down from heaven; by songs Circe transformed the comrades of Ulysses; with song the cold snake in the meadows is burst asunder.’

Wordsworth demonstrates again and again throughout the book his thorough knowledge of ancient literature, but more astonishingly, an understanding of the graffiti and the culture of writing on display on the walls of Pompeii that is not always found in later (dare I say, even recent) works on the Pompeian epigraphy. This is clear in his recording of the following text, one of many found in the Basilica. Here, the writer combined the words of two poets, Ovid and Propertius, who wrote similar entreaties regarding gifts, matchmaking, and the difficulties of love.

Ovid Amores I.8.77-78 and Propertius Elegies IV.5.47-48

CIL IV 1893 (CLE 1785)

Surda sit oranti tua ianua laxa ferenti

audiat exclusi verba receptus amans

CIL IV 1894 (CLE 1785)

Ianitor addantis vigilet si pulsat inanis

surdus in obductam somniet usqu[e] seram

‘Let your door be deaf to prayers but wide open to the bearer of gifts; let the lover who has been admitted hear the laments of the one excluded. The door-keeper must be awake for bearers of gifts, but when empty hands knock, let him be deaf and sleep against the bolt.’

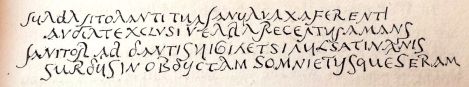

There are a number of things that I find remarkable about this book, and not just because I love a beautiful, old, leather-bound tome. One is the faithful rendering of ancient handwriting throughout the text, as seen in the photos above. Wordsworth does this for every grafitto he presents, both in Latin and in Greek, which presumably would not have been possible if he had not made a faithful rendering of each one at the time he visited Pompeii five years before writing. Considering many of the early visitors to the excavations were more interested in collecting images of themselves in a romantically ruinous vista, or, for those bent on more scholarly pursuits, reproducing the ancient artworks, this attention to the non-lapidary texts is an unusual occurrence. As a feature of epigraphic publishing, illustrations of the handwriting do not appear again for nearly forty years until the first volume of CIL IV, and even then, is not applied systematically until sometime late in the 20th century. Wordsworth also shows an astuteness in his observations on language and the literary nature of the texts. Not only does he recognise the origin of those he records, but he seemingly has no difficulty in discerning the accurate quotations from those that are adapted or conflated in some way. He remarks once or twice on the poor spelling of the texts (which he attributes to slaves), but does not assume this is due to illiteracy, but rather refers to it as the ‘false Latinity of an Italian scribe.’ He also remarks on the very nature of literacy itself (which is a topic I have been meaning to address myself at some point), and makes a point with which I strongly agree, that ‘We hear much of the diffusion of literary tastes among all classes of people in our own age and country; and comparisons, injurious to other nations and times, are founded on this assumption. This is hardly fair. I should much question whether all the walls of all the country towns in England, would, if Milton were lost, help us to a single line of the Paradise Lost.’

Wordsworth’s attention to the graffiti shows, in many ways, that he was ahead of his time, not just in the recording of the texts, but in his appreciation for them, for the literary and literate proclivities of the Pompeians, and for recognising what an important artefact these scratched words were. For that, I would argue anyone working on ancient graffiti or Pompeii owes him a great deal of admiration and gratitude.