Whilst other Americans are preparing to spend the day celebrating our nation’s independence with barbeques, beer, and fireworks, I started thinking about a slightly different colonial experience. Pompeii, like many other towns in southern Italy, rose up in rebellion against Rome during the Social War (90-88 BC). This was a war fought between many Italian territories who had previously been allies of Rome. Much like the American colonialists, they had become fed up with paying taxes, providing soldiers, and supporting the expansion of Rome without receiving benefits like citizenship and voting rights. Indeed, the Italians also had a problem of taxation without representation. The alliance between Pompeii and Rome prior to the outbreak of the war is largely unknown – there is no clear evidence – but Pompeii was, by 90 BC, more or less surrounded by cities that were beholden to Rome, and had been Romanised (at the very least in terms of the adoption of Latin). Regardless, Pompeii did join other Campanian cities in the fight against Rome. In essence, what the Italian people wanted was either full access to the rights and benefits of being a Roman citizen, or a cessation of ties and alliances all together.

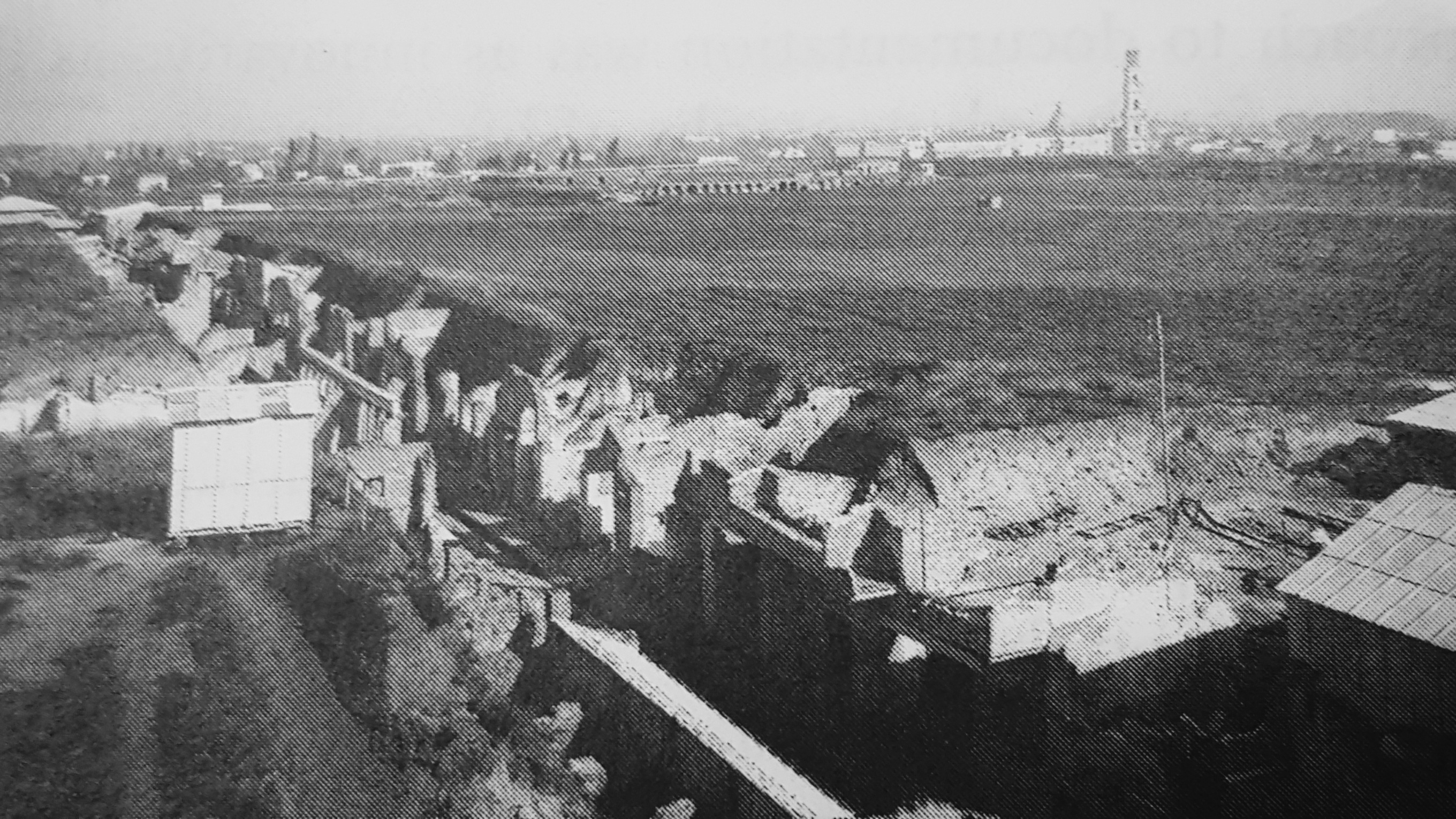

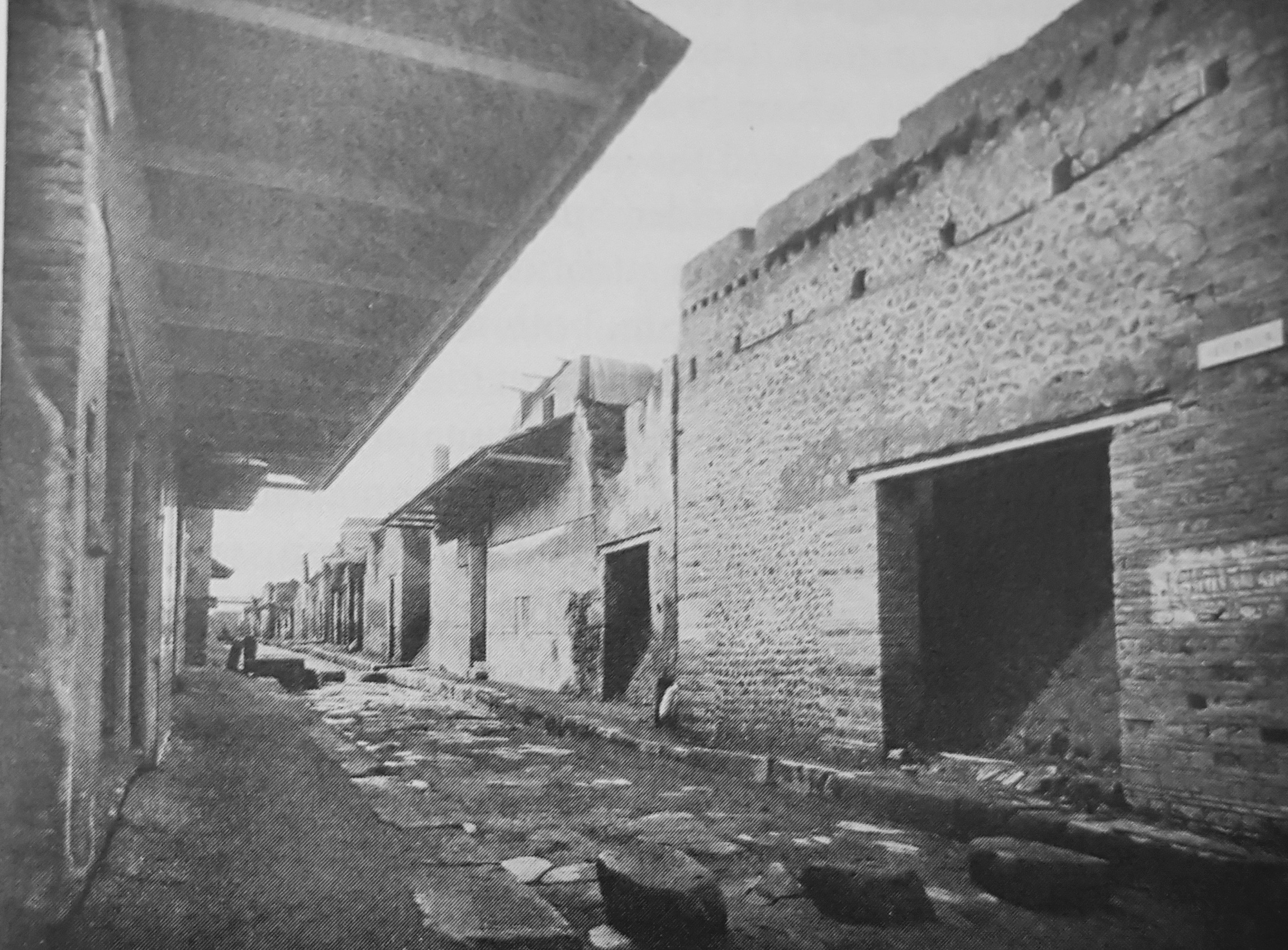

Besieged by Sullan troops in 89 BC, the city eventually fell to Rome. Evidence of the siege can still be seen in the city wall running between the Porta de Ercolano and the Porta del Vesuvio, and it is not uncommon for excavation in the northern sector of the city to turn up ballista and other projectiles used by the Roman soldiers.

The war was over soon thereafter. Despite being ostensibly won by Rome, the Italian allies got what they wanted: full Roman citizenship was granted to the entire population of Italy. There is a fair amount of debate as to what happened in the intervening years particularly as to how the city was governed, but in 80 BC, Pompeii officially became a Roman colony. The foundation of the colony was granted to Sulla, not only because he conquered the city, but as the general responsible for Roman troops in this and many other wars, he had a large number of veterans to provide for. It is from inscriptions such as this that we know the full name of the colony, which included reference to the founding patron:

The war was over soon thereafter. Despite being ostensibly won by Rome, the Italian allies got what they wanted: full Roman citizenship was granted to the entire population of Italy. There is a fair amount of debate as to what happened in the intervening years particularly as to how the city was governed, but in 80 BC, Pompeii officially became a Roman colony. The foundation of the colony was granted to Sulla, not only because he conquered the city, but as the general responsible for Roman troops in this and many other wars, he had a large number of veterans to provide for. It is from inscriptions such as this that we know the full name of the colony, which included reference to the founding patron:

CIL X 787

M(arcus) Holconius Rufus d(uum)v(ir) i(ure) d(icundo) tert(ium) / C(aius) Egnatius Postumus d(uum)v(ir) i(ure) d(icundo) iter(um) / ex d(ecreto) d(ecurionum) ius luminum / opstruendorum(!) HS |(mille) |(mille) |(mille) / redemerunt parietemque / privatum col(onia) Ven(eria) Cor(nelia) / usque at(!) tegulas / faciundum coera(ve)runt.

‘Marcus Holconius Rufus, duumvir with judicial power for the third time, and Gaius Egnatius Postumus, duumvir with judicial power for the second time, by decree of the decurions, paid 3,000 sesterces for the right to block off light, and say to the building of a private wall belonging to the colonia Veneria Cornelia.’

It is via Sulla that Venus becomes the patron goddess of the city, as she was also his family’s chosen deity. His moniker as ‘lucky’, a cognomen awarded to him (his full name was Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix) can also be found in the name of one of the districts around Pompeii, as attested in a number of inscriptions of its magister’s:

CIL X 1042

M(arcus) Arrius | (mulieris) l(ibertus) Diomedes / sibi suis memoriae / magister pag(i) Aug(usti) felic(is) suburb(ani).

‘Marcus Arrius Diomedes, freedman of a woman [Arria], for himself and his, in memory. Magister of the pagus Augustus Felix suburbanus.’

Roman colonies were typically founded with veteran settlement, and as far as anyone is aware, Pompeii was no different. This likely meant the arrival of approximately two thousand veterans of Sulla’s wars, with families if they had them, into the territory of Pompeii around 80 BC. Unlike places like Praenestae where soldiers were placed into towns abandoned by the previous inhabitants, it appears that the colonists and natives were integrated, at least physically. Pompeii was, in fact, the only colony of Sullan veterans that didn’t completely breakdown – there are examples of completely seperate cities, relocation of the native population, and at the worst, a significant amount of bloodshed. But that doesn’t mean that all went smoothly.

Approximately twenty years after the foundation of the colony at Pompeii, Cicero was called upon to defend Publius Cornelius Sulla, nephew, and at the time patron of Pompeii, against charges of conspiracy and incitement. The younger Sulla had previously had a spot of legal bother when he was elected consul and quickly removed from office for bribery, but in 62 BC was facing charges as a result of his supposed involvement in the Catiline Conspiracy. The passage of Cicero’s defense which relates to Pompeii is brief, and somewhat ambiguous:

Pro Sulla 60-62

‘Furthermore, I cannot understand what is the nature of this charge that the inhabitants of Pompeii were instigated by Sulla to join that conspiracy and set their hand to this nefarious crime. Do you think that they did join the conspiracy? Who ever said this, or was there even a hint of a suspicion of it? “Sulla,” he says “set them at odds with the new settlers in hope to use the division and dissension he had caused to get control of the town with the aid of the inhabitants of Pompeii.” In the first place, the whole quarrel between the inhabitants and the new settlers was reported to the patrons when it had grown chronic and had been pursued for many years. Secondly, in an inquiry conducted by the patrons, Sulla’s views were in complete agreement with those of the others. Finally, the new settlers themselves realize that Sulla was defending their interests no less than those of the inhabitants of Pompeii. This, gentlemen, you can infer from the large crowd of the settlers in court, men of the highest standing who are supporting and showing their solitude for their patron here in the dock, the defender and guardian of that colony. Even if they had not been able to preserve him in the possession of all his fortune and of every office, it is their urgent wish that at least in misfortune which now prostrates him he should through you be helped and kept from harm. The inhabitants of Pompeii who have been included in the charge by the prosecution have come to court to support him with no less enthusiasm. Although they quarrelled with the new settlers about promenades (ambulatione) and elections, they were of one mind about their joint safety. And I do not think that even this is an achievement of Publius Sulla that I should pass over in silence: that although he founded the colony and although political circumstances caused the privileged position of the new settlers to clash with the interests of the inhabitants of Pompeii, he is held in such affection and is so popular with both parties that he is felt not to have dispossessed the one but to have established the prosperity of both.’

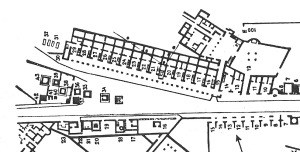

Much has been made by modern scholars as to the levels of discord that must have existed between the colonists and the native Pompeians. The reality is that little information is provided by Cicero other than the fact that there was a disagreement over voting rights and a public walkway (this has never been fully understood but I have always liked the idea put forward by T.P. Wiseman and Dominic Berry that this refers to the quadraporticus behind the small theatre), and that in his role as patron Sulla mediated a settlement between the two groups. As proof of this Cicero points out that both Pompeians and colonists are present at the trial supporting him. Others have floated the theory that the small theatre was built specifically to serve as a meeting place for the colonists. Whilst it was constructed, as we know from the dedicatory inscription, by two of the earliest magistrates of the colony, there is no evidence to suggest this purpose was intended or indeed realised. The only actual mention of the colonists that survives epigraphically comes from the amphitheatre, which was constructed by the same two politicians.

CIL X 852

C(aius) Quinctius C(ai) f(ilius) Valgus / M(arcus) Porcius M(arci) f(ilius) duovir(i) / quinq(uennales) colonia<e> honoris / caus{s}a spectacula de sua / pe<c>(unia) fac(iunda) coer(averunt) et colon{e}is / locum in perpetu<u=O>m deder(unt).

‘Gaius Quinctius Valgus, son of Gaius, and Marcus Porcius, son of Marcus, quinquennial duovirs, for the honour of the colony, saw to the construction of the amphitheatre at their own expense and gave the area to the colonists in perpetuity.’

The size of the amphitheatre (unlike the small theatre), in no way relates to the number of colonists, and could never be claimed to be solely for their use regardless of how the inscription is interpreted. The fact remains that if the colonists wanted to present a clear and long lasting physical imprint on the city in order to visually assert their dominance over the native population, they failed miserably. Indeed, not even a funerary monument remains that names a colonist of the Sullan settlement. As to the issue over voting rights, the little evidence there is of longevity amongst politically active families in the pre- and post-colonial periods suggests any impact of a change in regime does not withstand the first generation after colonisation.

The evidence, in all its forms, suggests a true and relatively peaceful integration of veteran colonists and the indigenous population, even though colonisation was a result of war. This was unusual for the time, and as today’s American holiday suggests, unusual even two hundred and fifty years ago.