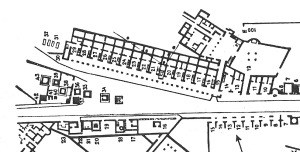

By now it seems the entire world is aware of the most recent discovery in Pompeii, a tomb located in the necropolis of the Porta Sarno to the east of the city. Having spent so many years investigating the funerary monuments of Pompeii myself, I am thrilled that new material is being excavated (even if it does make my book somewhat outdated. Hmm… second edition maybe?) I (along with others) have always known there were many, many more tombs to discover in the environs of the city. We should all do well to remember that modern Pompei sits atop most of ancient Pompeii’s dead.

There is, however, much excitement about this particular find, and rightfully so, because it contains a variety of evidence that is unique, and in some cases, previously unattested. Some of this new information comes from the inscription:

M(arcus) Venerius coloniae

lib(ertus) Secundio, aedituus

Veneris, Augustalis et min(ister)

eorum. Hic solus ludos Graecos

et Latinos quadriduo dedit.

‘Marcus Venerius Secundio, freedmen of the colony, guardian of the temple of Venus, Augustalis and minister of them. He, on his own, gave Greek and Latin games for four days.

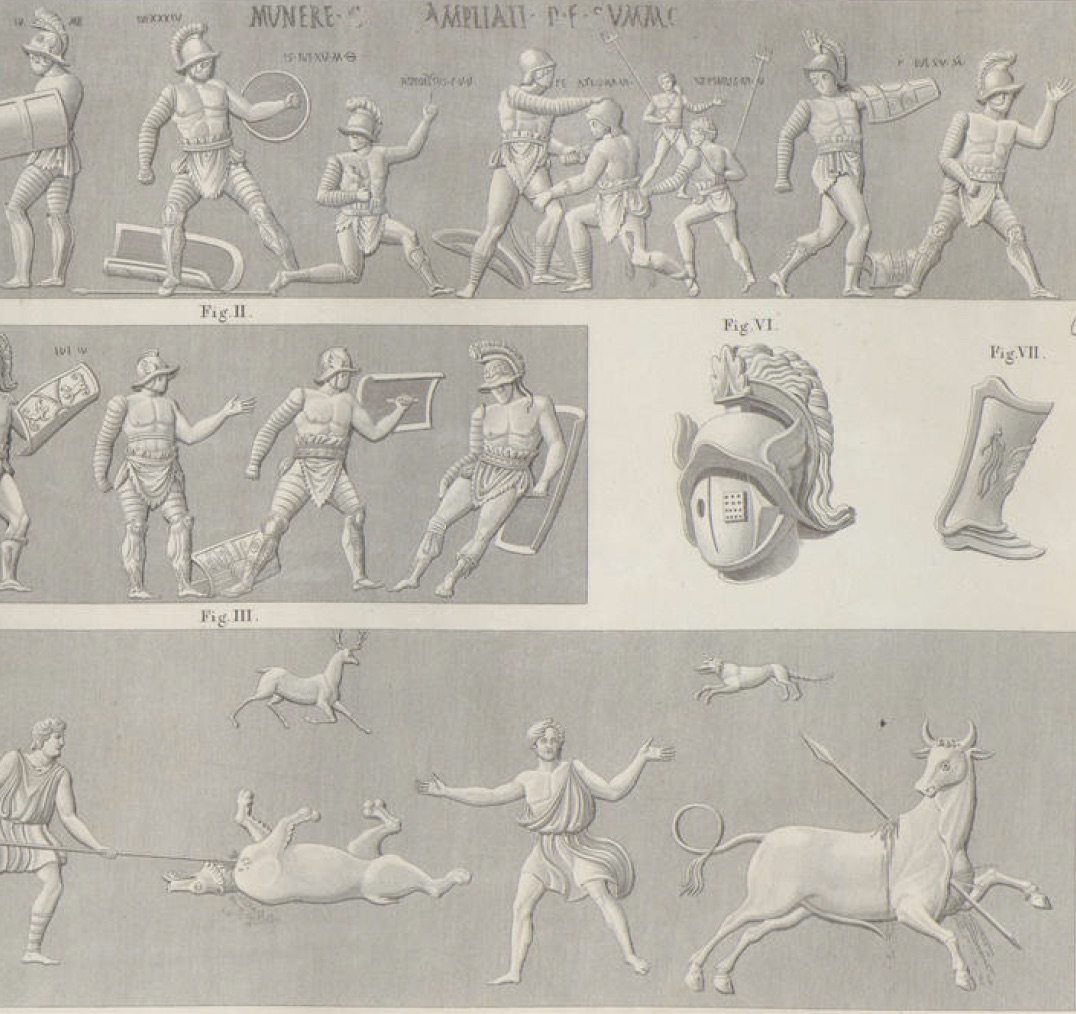

One item that has ancient historians taking notice is the specific mention of Greek games – something that has been speculated about but was heretofore unconfirmed as taking place in the theatres of Pompeii. Georgy Kantor provides a brief exposition on the significance of this. A freedman of the city, Venerius Secundio’s involvement in the worship of Venus, the patron goddess of Pompeii, the evident wealth he obtained that allowed him to sponsor entertainments, and membership of the Augustales are all elements that serve to enhance our understanding of the civic and religious life of the city (and thus, other communities in the Roman world.)

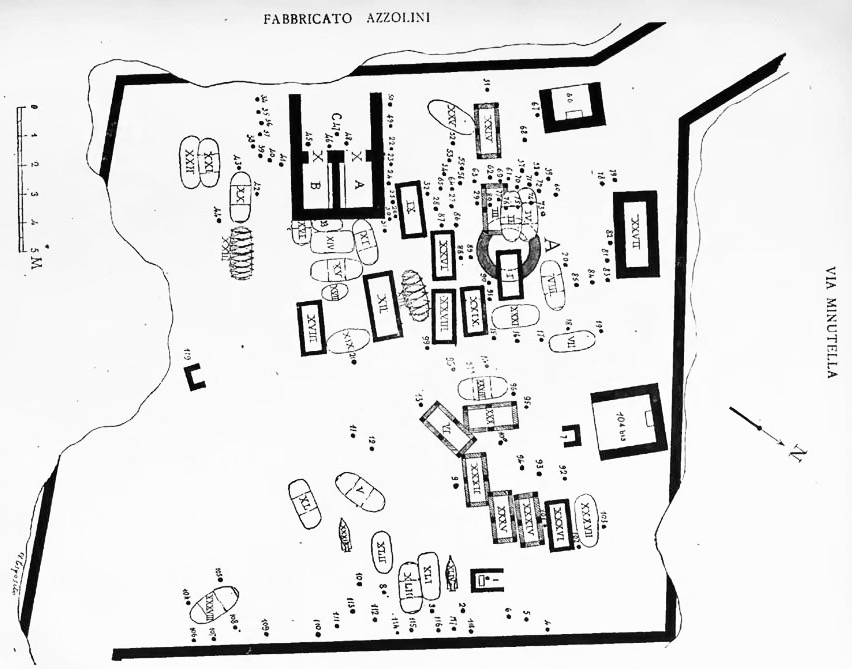

Marcus Venerius Secundio appears in only one other text from Pompeii, one of the wax tablets of Caecilius Iucundus (CIL 4.3340.139). He is included here with two other well known men – Decimius Lucretius Valens and Marcus Stronnius Secundus, which provides a date of the mid AD 50s. The tomb, as it has been described, probably dates to the 60s or early 70s. There is, however, further epigraphic evidence from the monument as a columella was also found marking the burial of a beautiful glass urn, bearing the name of Novia Amabilis. This is a new name to add to the Pompeian prosopography, as no female members of this gens are otherwise attested. There is a single graffito naming a Novius (CIL X 10136), and one naming a Lucius Novius Priscus.

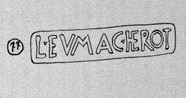

CIL IV 2155

C(aius) Cominius Pyrrichus et

L(ucius) Novius Priscus et L(ucius) Campius

Primigenius fanatici tres

a pulvinar(i) Synethaei

hic fuerunt cum Martiale

sodale Actiani Anicetiani

sinceri Salvio sodali feliciter.

Although there is some debate about how exactly this should be translated, the general consensus (which is not quite as cryptic as Franklin suggests) is that Novius Priscus and his friends Gaius Cominius Pyrrichus and Lucius Campius Primigenius, three rabid fans of Actius Anicetus, a well known pantomimist, greet some of their other mates. The idea of linking into the same family Novia Amabilis, buried in the tomb of a sponsor of Greek and Latin theatre spectacles and Lucius Novius Priscus, a devotee of a local star of the stage, is admittedly quite an attractive one.

Of course, the one thing I have not yet mentioned is the skeleton. Found in a small cell at the rear of the tomb, there is no doubt it is the best preserved set of human remains yet discovered in the ancient city. Hair! An Ear! Maybe DNA! Heady stuff, to be sure. But what I haven’t yet seen mentioned is what an anomaly it is to actually find a skeleton in a tomb in Pompeii. Prior to Roman colonisation in 80 BC, inhumation was the standard Samnite / Italic form of burial. Graves such as these have been discovered, but they weren’t monumental structures built (primarily) above ground. With the Romans came monumental tomb building and cremation. After all, there are two sets of remains found in the tomb of Marcus Venerius Secundio that are cremated, deposited in urns, including that of Novia Amabilis. What this means is a large above ground tomb from the Roman colonial period containing a skeleton is unheard of in Pompeii.

The simple fact of a skeleton existing in a Pompeian tomb (regardless of its state of preservation) is the most incredible thing about this latest find. I hope someone else notices that.

Edited to add: A new video has been released by the Parco Archeologico di Pompei that shows more clearly the small vaulted chamber that contains the skeleton, which was hermetically sealed when excavated. This shows that this is, in fact, an intentional inhumation and reveals a new type of burial, never seen before in Pompeii.