Earlier this week it was announced that the Italian Ministry of Culture is planning to build a floor in the Colosseum. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the reaction from archaeologists and historians is a bit mixed. There is an understandable concern about the mechanisms of the floor and the impact on the structure. How the floor is integrated into the existing architecture is one issue, but the potential harm of the footfalls of the annual influx of six million tourists across the floor, or future structural changes necessary to host cultural events or re-enactments is also a necessary consideration. The official statements about the floor have attested to a low-impact and sustainable plan, going so far to say that the floor could be removed in the future with no lasting effect on the ancient remains. Their aim is to not only provide the view from the centre of the arena floor that those engaged in ancient games would have had, but also to allow the amphitheatre to be used for modern stagings. This is hardly a new or innovative idea: the theatres in Pompeii and Verona have been renovated and used in this manner for years. In the most general terms, as far as it is possible to discern from the limited information, this seem like a very good thing.

What surprised me was that a fair bit of the negative reaction to the plan is that there should be a floor at all, as if this will somehow diminish the experience of the Colosseum as a whole. I found this to be at odds with the design, which seems to be comprised of wooden slats that can be rotated and retracted, thus allowing a view into the hypogeum below, as well as to open the subterranean galleries up entirely.

A full video of how this will work, from which the above images were taken, can be viewed here.

Late on the day of the announcement I was contacted by TimesRadio for an interview about this. I had a very (very!) brief conversation with John Pienaar (somewhere around the one hour mark) about the way the subterranean level of the amphitheatre was used by the Romans. (And yes, of course Gladiator was referenced, but not by me.) Not knowing what I was going to be asked, I had a quick review of Colosseum facts, and this only furthered my consternation about objections to the idea of a floor. The Flavian Amphitheatre, as it was designed in the first century AD, had a floor. In fact, the floor existed for centuries, and it wasn’t until the early twentieth century that hundreds of years of debris and accumulated detritus were finally removed from the ancient floor and subterranean space of the hypogeum. In other words, the Colosseum has had a floor for significantly longer than it hasn’t had one.

The Colosseum was used, as originally intended, for about 500 years. The floor and the hypogeum were integral to putting on the gladiator contests, hunts of wild animals, and sea battles that were held there. The subterranean structures were, as I said on the radio, akin to the backstage elements of a modern theatre: scenery and props held at the ready, places for the next performer to wait (whether man or beast), utilising a series of trapdoors, cages, pulleys and weights, and tunnels connected to the gladiator barracks of the Ludus Maximus across the street, as well as to the stables for the animals. As with any large, heavily used building, there were repairs and alterations made at many points, some the result of the changing needs of those using the structure, some as a result of disasters like earthquakes and fire. A lightning strike caused a fire in AD 217, according to Dio Cassius (78.25), destroying upper levels of wooden seating that was not fully repaired for decades. The last record of repairs were for damage caused by an earthquake in 484, when the consul Decius Marius Venantius Basilius erected an inscription to record this work (CIL VI 1716). Gladiator fights were banned in the late 4th century and again in the 5th, but wild animal hunts continued well into the 6th century, when the consulship of Anicius Maximus was celebrated with such an event.

After that…. ? The bare bones of the Colosseum survive, but it is re-used and abused for centuries. It is rumoured it became a dumping ground for the bodies of criminal elements in the Middle Ages. One end housed a religious order from the mid-14th until the 19th century. There were workshops and a Christian shrine, and at one point, a fortress housed by nobles. The building itself was stripped, the spolia of travertine and marble used to build elsewhere, or burned to make quicklime. The bronze clamps holding the stonework together were also stripped for use. Another earthquake brought down the southern side of the building in the 14th century. This is why the Colosseum appears as it does today – no longer a gleaming white façade, pockmarked and scarred. In the 16th century the Church got interested, and tried to use the building for new purposes. Pope Sixtus V wanted to turn it into a wool factory to employ the prostitutes of the city, which I think unsurprisingly, failed. In the 17th century a cardinal suggested holding bullfights, but this was an unpopular suggestion. It was in the 18th century that the Colosseum was endorsed as a sacred site for Christians, with Pope Benedict XIV forbidding its continued use as a quarry and consecrating the building and including it in the Stations of the Cross, a tradition that still continues today as part of the processions held on Good Friday.

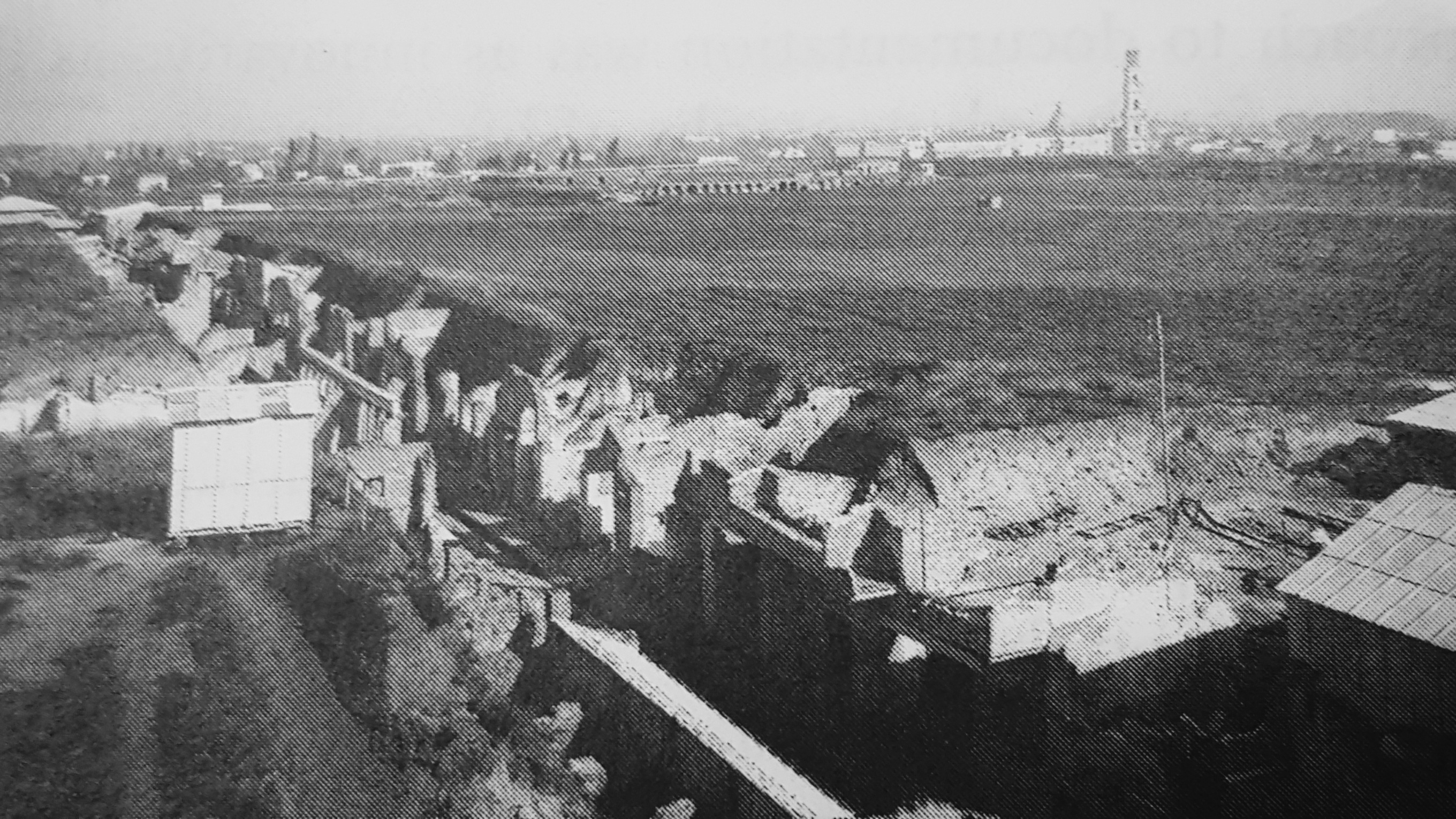

It wasn’t until the 19th century that interest in the Colosseum as an ancient artefact really took hold. It was then that the first works were undertaken to repair the structure, shoring up both the exterior walls and repairing the interior. This included the first attempts to clear the hypogeum, which had, in the intervening centuries, become well-documented for its abundance of different species of plants. From the first attempts to catalogue the flora, more than 600 types were identified. Eventually, this too was a concern, because of the destructive impact the vegetation had on the structure itself. And so, from the mid 1800s, any remaining bits of floor and the debris accumulated in the substructure were cleared. The project was finally completed in the 1930s during Mussolini’s push to reinvigorate Ancient Rome.

The Colosseum, as anyone has experienced it over the last century, is not what it was. Adding a floor is, in some ways, a small step towards repairing what is lost, and does offer a potential to use the space in a way it hasn’t been for centuries. Monuments are, as odd as it sounds, ever changing. I have been to the Colosseum enough times over the years to have been there when there was no flooring at all, when the hypogeum was closed to the public, and when the upper levels were forbidden. All of those things have changed since I first went to Rome in high school. More to the point, I keep comparing my memories of my visit down into the hypogeum (with the expert on the subject no less) to that of one to the other Flavian amphitheatre, the one in Pozzuoli. It has a floor. It has a similar substructure. Being in the enclosed space of that hypogeum, wandering in and out of the cells and cages, feeling a bit lost in the relative dark and small space, gave me a huge sense of what it was like to be down there two thousand years ago. I can’t help but think that experience is one worth replicating in Rome.

© Victoria & Albert Museum, London

© Victoria & Albert Museum, London