Today marks an odd sort of anniversary for me: sixteen years ago I arrived in the UK, with the intention of completing a MA and returning home to the US at the end of a year. Clearly, that didn’t quite go to plan, and here I remain. Earlier this month, I became a British citizen. In many ways this was a decision made for practical and legal issues rather than a sudden overwhelming desire to be British, but the ceremony itself, in conjunction with a number of other issues currently in the forefront of my native country, got me thinking about what it means to be a citizen of any place, at any time, and how the concepts of citizenship, nationalism, and patriotism can become so muddled.

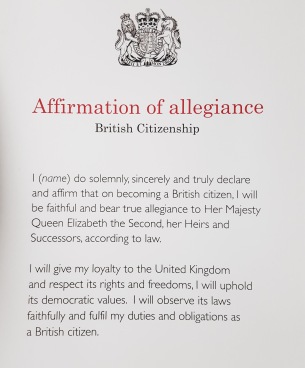

In the defensive action that made Cicero’s career, In Verrem (II.5.162), Cicero described an event of a man being beaten who defends himself with the words ‘Civis Romanus sum.’ He believed his claim to Roman citizenship was enough to protect him from torture and death. This idea has resonated politically – it was quoted by Lord Palmerston in a speech to Parliament in 1850, is the basis of President Kennedy’s ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’ speech, and was referenced by (unfortunately) fictional President Jed Bartlett in The West Wing. However, Cicero also said ‘But no one who had any acquaintance with our laws or our customs, who wished to retain his rights as a citizen of Rome, ever dedicated himself to another city.’ (Pro Balbo 30). I’ve not only dedicated myself to another country, but to another ruler and thus, in essence, form of government. As part of becoming a citizen of the UK, I had to swear the following oath:

This is interesting for a number of reasons. It is asking naturalised citizens for an oath that is not demanded of the born citizenry. Not only is there no request for such an oath if born here, but there are many Brits of a pro-Republic leaning who would balk at promising allegiance to the monarchy, and thus wouldn’t be able to fulfill the same requirement asked of someone willingly choosing to become a citizen. More to the point, however, it reminded me of another oath, one sworn by citizens of Paphlagonia in 3 BC:

Paphlagonian Oath OGIS 532.

‘In the third year after the twelfth consulship of Imperator Caesar, son of the god, Augustus, on the day before the nones of March at Gangra in the market place, this oath was sworn by the inhabitant of Paphlagonia and the Romans who do business in the country.

I swear by Zeus, Hera, the Sun, and all the gods and goddesses, and Augustus himself, that I will be loyal to Caesar Augustus and his children and descendents all the time of my life by word and deed and thought, holding as friend whomsoever they so hold, and considering as enemies whomsoever they so judge, and for their interests I will spare neither body nor soul nor life nor children, but will endure every peril for their cause. If I see or hear anything being said or planned or done against them, I will lay information and I will be the enemy of such sayer or planner or doer; whomsoever they themselves judge to be their enemies, them I will pursue and resist by land and by sea, with arms and with iron. If I do anything contrary to this oath or not according as I have sworn, I invoke death and destruction upon myself and my body and soul and children and all my race and interests to the last generation of my children’s children, and may neither the earth nor the sea receive the bodies of my family and my descendants, nor bear crops for them.

The same oath was sworn by all the rural population at the shrines of Augustus in the districts beside the altars of Augustus.’

This was a remarkable thing at the time – wherein citizens of a province were required not to swear an oath to Rome – but to a single man, Augustus. Cicero’s concept of Roman citizenship seems to have been superseded by a notion of patriotism, that is, loyalty to country, fatherland, and etymologically, ultimately the father. Augustus was, after all, named Pater Patriae by the Senate in the following year. The notion of being a citizen of Rome seems not to have changed much on the ground (as far as the evidence reveals), but the ideas of what that means and to whom one is loyal fundamentally shifts with the onset of empire.

I think, in essence, the idea of empire and monarchy are what Rome and Britain have in common in terms of what they ask of their citizenry, both natural born and naturalised. I am not quite sure if the same can be said of the US. In the years I have lived in the UK, I have become aware of an acute difference between what for Brits is nationalism (especially in regards to identification as English, Welsh, etc.), and for Americans is patriotism. The American idea of patriotism (so many flags!) is one I have struggled to negotiate most of my life, and has recently become a larger issue as part of protests arising around the national anthem, the Black Lives Matters movement, and other social injustices. And yet, no one (as far as I am aware), who knows I am now a citizen of two countries has called into question my allegiance to either.

Regardless, I am keenly aware that whatever passport I hold, on some level I will always be identified as an American, and not British. Cicero would probably have a few choice words for me, but somehow, I think the Paphlagonians might be more understanding.

Does being dual mean that you’re neither? Is it now you accent that fuels people’s assumptions?

More frivolously, have you started chucking in ‘U’s more often and held back on ‘Z’s? 😉