In the U.S., today, the Friday after Thanksgiving, is commonly known as Black Friday – a retailers dream (or nightmare) – as it is the day that traditionally kicks of the Christmas shopping season. It has become so ubiquitous a term, it began to appear in advertisements for sales here in the U.K. last year, and this year, has begun more than a week in advance of the day itself (and let’s not even discuss the number of emails I’ve had today from various shops). Whilst the last decade or so has shown a dramatic shift to shopping online rather than actually leaving the house, in the past, both recent and distant, shopping, for foodstuffs at the very least, was virtually a daily activity.

Shopping for various goods – pots, clothing, shoes, food items – is part of a lively scene depicted in a wall painting that shows the Forum. Found in the Praedia of Julia Felix (II.iv), this is often used as an illustration of the activities of daily life in Pompeii.

It is not clear if this painting represents a nundina (market day) or just an average day. It is believed that the large regional market days would have been held in or around the amphitheatre, which is a significantly bigger space. There are a series of painted inscriptions that seem to demarcate areas for particular stall holders in arcades of the amphitheatre, such as this example:

CIL IV 1096

Permissu / aedilium Cn(aeus) / Aninius Fortu/natus occ(u)p(avit).

‘By permission of the aediles Gnaeus Aninius Fortunatus occupies (this space).’

The market was a regional one, moving from town to town on set days. A text from a shop (III.iv.1) provides the calendar:

CIL IV 8863

Dies / Sat(urni) / Sol(is) / Lun(ae) / Mar(tis) / Merc(urii) / Iov(is) / Ven(eris) // Nundinae / Pompeis / Nuceria / Atilla / Nola / Cumis / Put<e>olis / Roma / Capua // X[VIIII] / X[VIII] / X[VII] / XV[I] / XV / XIV / XIII / X[II] / XI / X / VIIII // VIII / VII / VI / [V] / [I]V / [I]II / II / pr(idie) / K(alendae) / Non(ae) / VII / VI // Non(ae) / VIIII // VIII / VII / VI / V / IV / III / pri(die) / Idus // I / II / III / IV / V / VI / VII / VIII / VIIII / X / XI / XII / XIII / XIV / XV / XVI / XVII / XVIII / XVIIII / XX / XXI / XXII / XXIII / XXIIII / XXV / XXVI / XXVII / XXVIII // XXVIIII / XXX.

Day Markets

Saturn Pompeii, Nuceria

Sun Atella, Cumae, Nola

Moon Cumae

Mars Puteoli

Mercury Rome

Jove Capua

Venus

Whether the person who scratched this into the wall was using this as a personal or commercial reminder is unclear. Information about the purchase and sale of goods, including slightly fluctuating prices depending on the day, is detailed in an inscription (IX.vii.24–5). Found in the atrium of a inn, attached to a bar next door, this graffito was clearly the inventory list of the owner/operator.

CIL IV 5380

VIII Idus casium I / pane(m) VIII / oleum III / vinum III / VII Idus / pane(m) VIII / oleum V / cepas V / pultarium I / pane(m) puero II / vinum II / VI Idus pane(m) VIII / puero pane(m) IV / halica III / V Idus / vinum domatori |(denarius) / pane(m) VIII vinum II casium II / IV Idus / Hxeres |(denarius) pane(m) II / femininum VIII / tri<t>icum |(denarius) I / bubella(m) I palmas I / thus I casium II / botellum I / casium molle(m) IV / oleum VII / Servato / montana |(denarius) I / oleum |(denarius) I VIIII / pane(m) IV casium IV / porrum I / pro patella I / sittule(m) VIIII / inltynium I / III Idus pane(m) II / pane(m) puero II / pri(die) Idus / puero pane(m) II / pane(m) cibar(em) II / oleum V / halica(m) III / domato[ri] pisciculum II.

‘7 days before the Ides cheese 1, bread 8,oil 3, wine 3.

6 days before the Ides bread 8, olive 5, onion 5, cooking pot 1, bread for slaves 2, wine 2.

5 days before the Ides, bread 8, bread for slaves 4, porridge 3.

4 days before the Ides, (unknown type of wine) 1 denarius, bread 8, wine 2, cheese 2.

3 days before the Ides [?] bread 2, female? 8, wheat 1 denarius, beef? 1, dates 1, incense 1, cheese 2, small sausage 1, soft cheese 4, oil 7.

For Servatus [unknown item], oil 1 denarius, 8 bread 4, cheese 4.

Leek 1, for a small plate 1, [two unknown items].

2 days before the Ides, bread 2, bread for slaves 2.

1 day before the Ides, bread for slaves 2, plain bread 2, leek 1.

On the Ides plain bread 2, oil 5, porridge 3, whitebait 2.’

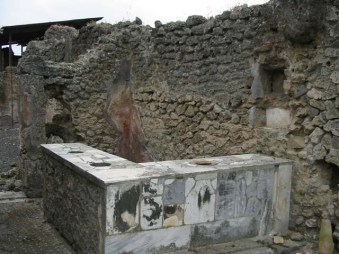

Besides functioning as accommodation for the night, the various taberna and thermopolium found in abundance in Pompeii such as this one served both hot and cold food. The counter tops, such as the one located in this building, are more often than not the identifying feature of such services.

Their prevalence in Pompeii, as established by Steven Ellis, and still part of ongoing fieldwork by the Pompeii Food & Drink Project, has led to the conclusion that many of the city’s residents may have been getting their hot meals from such facilities, and did little cooking at home. That bread was a daily purchase has long been established: the large number of mills and bakeries in the city is well documented (thirty-three is the current tally). Selling bread is, in fact, commemorated in another wall painting, this one found in the (understandably named) House of the Baker (VI.iii.3).

There is additional evidence bread was sold from temporary stalls around the city, and not just for personal consumption. Two graffiti from the Temple of Apollo inform us that man named Pudens and Verecunnus were selling libarius, bread used in sacrifice (CIL IV 1768, 2769). The sale of other food items, particularly wine and garum, the fermented fish sauce so popular in Roman cooking, can be found on the amphorae recovered in excavation. These were typically marked with abbreviated texts indicating the name of the producer or owner, the origin, and contents of the jar.

CIL IV 9406

G(ari) f(los) scombr(i) / Scauri / ex officina Scauri / ab Martiale Aug(usti) l(iberto).

Scaurus’ finest mackerel sauce from Scaurus’ workshop by Martial, imperial freedman.

Garum manufactured by the Umbricius family was a particularly popular item both locally and elsewhere: approximately 23% of the jars containing fish sauce that have survived antiquity come from the Pompeian factory. The tituli picti are even commemorated in a mosaic in the Umbricii house (VII.vi.16).

Evidence for the buying and selling of other items that don’t necessarily survive as objects, such as textiles and luxury items like jewellery, can be found in some of the tablets of Iucundus as well as other graffiti. Items were either auctioned off or, occasionally, used as surety for borrowing funds. One example of this is recorded in a graffito in which a woman, who seems to be acting much like a modern pawnbroker, offers a loan in exchange for a pair of earrings:

CIL IV 8203

Idibus Iuli(i)s / inaures pos(i)tas ad Faustilla(m) / pro |(denariis) II usura(e) deduxit aeris a(ssem) / ex sum(ma?) XXX.

’15 July. Earrings deposited with Faustilla. Per two denarii she took as usury one copper as. From a total (?) 30.‘

Fortunately for the Pompeians, it seems they didn’t go in for the insanity of modern special sales, but went about their shopping, whether daily necessities or luxury items, with little fuss. Like most pre-industrial societies, for the majority of people, shopping was based on current necessity, and was done in moderation. Perhaps this changed in times of crisis, particularly when there were shortages of grain, when riots and fighting are recorded in Rome. Last I checked, however, there was no shortage of giant tellies or iPads. Maybe we should follow the ancient example and make this Friday a little less black.